“The land shapes people, but people also shape the land.”

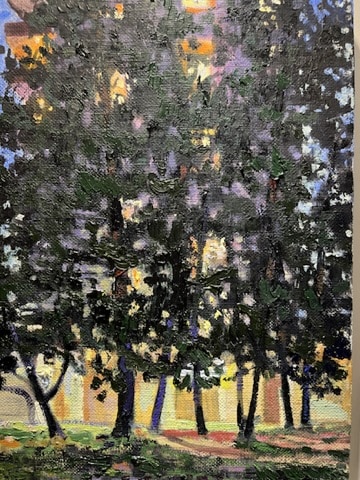

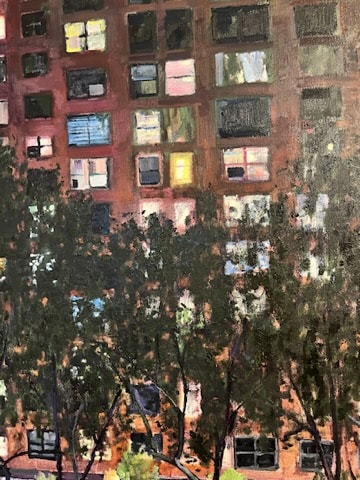

For contemporary Canadian artist Jeremy Herndl, painting is a tool for experiencing a place. Jeremy’s research centres around intersubjectivity and perception, ecology, and the intelligence of natural processes; the politics and legacies of the land, such as the ravages of colonialism, property and privilege, industry and gentrification. All these inform his contemporary approach to en plein air painting.

While his is a personal and meditative practice, it is not authorial. Rather, Jeremy aims to be a witness to the agency of place in these times of ecological trouble. Jeremy’s paintings are always about people, whether they feature overtly in the subject matter (urban, re-wilded, still life) or are simply implied in depictions of endangered forests and ecosystems in transition.

Painting on-site through direct observation, Jeremy is able to witness the changes in light and colour over the hours and days. He is able to interact with the humans and the creatures. Painting is a medium at that intersection of place and painter, two terms that are mutually defining.

This reciprocal relationship between individual and environment embraces the shifting appearances and interactions that occur over days and weeks. The process becomes like a conversation, the culmination of hours of attention and consideration.

Herndl’s latest exhibition, You Are Here, is an invitation for the viewer to visit with the places he paints by looking at these artworks and having a conversation of their own. On July 12, 2023, ArtRow sat down with Jeremy and chatted about his art and practice.

AR: Your work is beautiful!

JH: I never set out to make it beautiful. But if I can get into the space of really looking and really paying attention to what I’m looking at and articulating that looking through the touch of paint, then I think it just becomes beautiful.

Because it’s not just me. It’s this place that’s participating. If it was all up to me, it wouldn’t look very good. When we’re studying and looking at beautiful forests that are millennia old, it’s good to keep that on the top of our minds. The human element and what that means. I just want to say that, in every single painting, it’s always about humans. Even if there are no humans present, it’s always about humans.

From the time I was zero to the time I was a teen, I grew up living a very itinerant life. We moved many times, and I went to many schools. We lived throughout Surrey and then the lower mainland and Brackendale and Squamish and then Toronto, Ontario, and various parts of Ontario—Brampton, Bramalee, Etobicoke. We moved, I think my sister and I counted it, 30 times or something, but one of the formative, really important times for me was when we lived near Alice Lake Park in Brackendale, BC, which is near Squamish.

My great-great-grandfather was the first settler there, and so we have this family history there, and then my great-grandmother bought some property up near Alice Lake Park and we lived off-grid up there for a couple of years. I often say that that’s where I learned how to talk to trees.

AR: When did you know that you wanted to be an artist?

JH: Well I was always making art, I was always drawing and I used it as a way [to communicate]. It was the only thing I had. I didn’t have toys, I didn’t have things. Drawing was very portable and personal, and I used it to try to communicate to my mom that I wanted to go back to the bush.

I started to take it very seriously, and I started painting in the Kootenays around 16 or 17 years old, so I guess I was around 16 when I knew I wanted to be an artist

AR: What made you decide on painting as your medium of choice?

JH: For several years before art school, I was drawing constantly. I always carried a sketchbook around. I would draw my foot, my hand, an ashtray, some people across the street, buildings…because I really wanted to be able to understand how to draw what I see. That translated into painting pretty readily, because I wanted to render what I was seeing.

Drawing is interpretation, too, but for me, the painting takes everything a little bit further. You add the possibility of color, you can build space with color, with the paint itself, the material, thin versus thick. It just seems [to be more], paint is very readily available to articulate texture and the more visceral feeling of looking.

AR: Could you point to something specific that might drive your work? Or is there something specific that, at the moment, maybe, preoccupies you?

JH: When I was little and we were living up in the bush near Brackendale, we were living on my great-grandmother’s property. She was a naturalist, and we lived in the forest so there were lots of interactions with animals. But she was also a writer and a painter. I remember her giving me my first art lesson when I was about six, probably, and it was a painting that she had made of some cows in a meadow, with the forest behind it, and the snowy mountain peaks in the distance.

She saw me looking at this painting and she said, “Did you know that milk comes from the mountain tops?” She explained that it snows in the mountains, and then the snow melts into creeks and rivers, and then the creeks make the meadows green, and the cows eat the grass, and then we milk the cows. I remember that blew my little mind.

I think that’s one of the things you can be aware of: all the histories and all the things that have happened, whether it’s detritus or re-wilding or ecosystems failing or ecosystems recovering. That’s kind of how I feel about making these paintings and wanting to tell these stories. It seems like how we’re all connected and in nature.

AR: What do you think are some of the challenges and some of the possibilities in today’s art market, and the possibilities that exist for artists?

JH: I feel like with technology, I have basically my own global outreach device in my back pocket. I can take a really high-resolution photo of my work and post it, and also talk about what motivated the work. [It’s like] how technology has democratized the music industry. People don’t need a recording studio, you don’t need a movie production company or anything like that. I think the same thing is happening now for visual art.

On the other hand, it seems to me that visual art is a very exclusive kind of market. [There are a lot of obstacles if you want to] be represented by a really great gallerist, and galleries are also fewer and far between. It’s like all the stars have to align.

AR: What was your experience with Fairy Creek?

JH: I think that a sensitive landscape painter becomes conscious of the politics of land, the histories of land. This starts with colonialism, privilege, ownership, industrialization, gentrification, poverty, homelessness, and also resource extraction. I’ve become really sensitive to injustice when it comes to what I observe about the land.

When I made the painting of a tent city, I wanted to engage directly with what I saw. It’s an old, old concept, but landscape and power are intertwined and human histories are intertwined in the land. So, because of that, I felt that the industry has no right to take the last bit of old growth that’s left.

These last vestiges of old growth forest, they don’t just belong to the industry that feels entitled to take it…They are the biome that we depend on.

* * *

Jeremy Herndl

Canadian (1972)

Born in Surrey, British Columbia, Herndl received his MFA from Emily Carr University of Art + Design in 2011 and his BFA from NSCAD in 1996. The recipient of many grants and awards, Herndl most recently received the Helen Frankenthaler Fellowship (2019), the BC Arts Council Research and Development Grant (2018) and the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundations Grant (2017). Since 2010, he has participated in exhibitions at the Surrey Art Gallery, Open Space Art Society, Two Rivers Gallery in Prince George, BC and GoCart Gallery in Visby, Sweden.

His work is in permanent collections across North America and Europe, including the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Surrey Art Museum, The University of Victoria, The City of Victoria, The West Vancouver Museum, The City of Surrey, The Alberta Foundation for the Arts, and The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Internationally, his work is in corporate and private collections across the USA and Europe, including Brucebo Foundation and Koncepthus in Sweden.

Interview with Jeremy Herndl, Fortune Gallery, “You are Here,” July 12, 2023.

Citations: https://jeremyherndl.com/home.html