Non-indigenous people compulsively link “tradition” to Indigenous peoples and equate indigeneity with spirituality above all else. When First Nations peoples and art are assumed to be traditional, we effectively negate the distinctly non-traditional violence of European contact and the non-traditional world in which we all currently live – one of technology, digital innovation, and late capitalist globalization. How can we look at Indigenous art in a way that explores traditional art practices and acknowledges notions of cosmology, for example, but at the same time, resists the colonial gaze?

The term “contemporary-traditional,” while seemingly paradoxical, provides a framework for starting to look at Northwest Coast Indigenous art in new ways. Traditional elements of First Nations’ artmaking (carving, animal symbols, geometric forms) point to deeply-held Indigenous beliefs and, while an understanding of these elements is important, if taken alone, we miss crucial meanings. What is also required is a critical examination of the contemporary context, specifically: the degradation of nature, stolen and occupied land, and the epidemic of sexual, physical, and emotional violence against Indigenous peoples, and women and girls, in particular. When we look at contemporary art by Indigenous artists through the double lens of the “contemporary-traditional,” we can start to see the power and importance of these works.

Ancestral Practices and Artistic Renewal

No timid dwellers these, children of the wild coast, born between the sea and the land, to challenge the strength of the stormy North Pacific and wrest from it a rich livelihood. Their descendants would build on its beaches the strong, beautiful homes of the Haidas and embellish them with the powerful heraldic carvings that told of the legendary beginnings of the great families, all the heroes and heroines, the gallant beasts and monsters that shaped their world and their destinies. For many, many generations they grew and flourished, built and created, fought and destroyed, lived according to the changing seasons and the unchanging rituals of their rich and complex lives.

– Bill Reid (Haida) and poet Robert Bringhust

Contemporary Northwest Coast Indigenous artists are actively engaged in a process of cultural renewal. Colonial suppression resulted in interrupted, damaged, and halted traditions and practices (potlatches, familial story-telling, and most profoundly, languages). Tradition has not been a straight line – it was interrupted – and now, artists are excavating and adapting traditional forms and stories in an act of renewal. In this sense, we can understand “tradition” as a more fluid practice and, in the case of Northwest Coast indigenous art, one that moves between time and history.

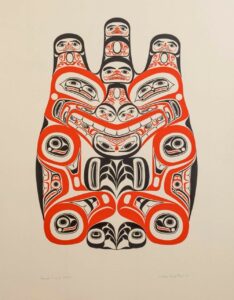

Haida artist Bill Reid was an early practitioner of formline design and his images were part of early renewal. In the silkscreen print, Haida Grizzly Bear (1973), for example, Reid evokes the interconnectedness of the animal and human world. Humans, birds, and animals are interlocked and intertwined in red ovoids and within thick black lines. Like a tapestry, the image provokes the viewer to consider each element of the larger whole, thus implicitly reminding us that humans and nature are connected.

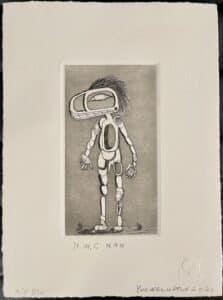

Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun is of Coast Salish and Okanagan descent and he passionately refutes the notion of “tradition.” His work can be seen to epitomize renewal in that he takes forms from Haida, Coast Salish, and canonical Canadian art (Emily Carr, for example) to create pastiches that simultaneously reference the violence of colonialism, the destruction of the land and Indigenous spirituality and beliefs. In the etching N.W.C. Man (2021), a hybrid human-raven figure stands as a symbol of the power of transformation and its hollowed-out formline ovoids provoke the viewer to ponder the meaning of this image.

In these works by Reid and Yuxweluptun, formline design and its ovoids, u-form shapes, and crescents have been used to represent transformation. While transformations point to the interconnectedness of all things, they’re also cries for profound paradigm shifts in the face of the current climate emergency and planetary extinction. “Extinction” is a loaded term with reference to Indigenous peoples because it was indeed the purpose of the colonial project. Indigenous peoples did not go extinct and formline design is evidence of this – its compositions represent the vitality, resilience, and diversity of Indigenous peoples.

Preserving Cultural Heritage and Reimagined Futures

The Coast Salish peoples are a cultural unit comprised of people who speak many different languages (hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, Straits Salish, Squamish, Nooksack, Chinook, to name a few) and lied in a region with congenial climate and rich natural resources. Retention of their distinct languages was consistent with a pattern of great linguistic diversity among the Coast Salish as a whole, a diversity that attests to lengthy and relatively stable occupation of their territory.

– Susan Point (Coast Salish)

The resurgence of art has also led to renewed efforts in preserving and revitalizing cultural traditions. Many Indigenous artists actively engage in mentorship programs, passing on their knowledge and skills to younger members of their communities. By doing so, they ensure that the cultural legacy and artistic techniques are kept alive for future generations.

Kwakwaka’wakw artist Quinn James has been trained within his own community and his carving represents forms and subjects specific to his Nation. Quinn’s Orca Mask (2021) uses carved cedar and bark to represent a human-orca transformation. A whale fin emerges from a human face as if to penetrate upwards through the sea and, in this hybrid form, the significance of the orca imbues the individual with mythical traits of the whale: strength and wisdom.

While Quinn was trained by his hereditary masters, Coast Salish artist Susan Point has worked to recover lost knowledge about her ancestors in order to find her own visual art practice. In the silkscreen print, Beyond the Edge (2018), Point’s circular composition, in addition to representing the life force of nature, references Coast Salish spindle whorls traditionally used for weaving. Used primarily by women, spindle whorls have created textiles and imagery of great cultural significance and its circular shape stands as a powerful symbol for Coast Salish peoples.

Contemporary Northwest Coast Indigenous artists, such as Susan Point, Robert Davidson, James Quinn, Dylan Thomas, KC Hall, LessLIE and many, many more, are enlivening ancestral themes and forms and developing new artistic practices and visual languages. Their carvings, prints, and paintings are a powerful testament to the resilience of this region’s peoples and cultures and, imbued with tradition and memory, the works stand as new visions for the future.

Please click here to view our related exhibition Contemporary Northwest Coast Indigenous Art: Visual Languages and Symbolism.

Works Cited + Additional Reading:

https://salishseasentinel.ca/2016/10/salish-eagle-to-glide-over-the-salish-sea/

Listening to Our Ancestors: The Art of Native Life Along the North Pacific Coast. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian.

Native North American Art, Janet Catherine Berlo & Ruth B Phillips

Hare, J. (2002). Pushing the boundaries of tradition in art: An interview with susan point. BC Studies, (135), 163-175. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/pushing-boundaries-tradition-art-interview-with/docview/196886036/se-2

Young, I. R. (2017). Cultural imPRINT: A history of northwest coast native and first nations prints (Order No. 10642024). Available from ProQuest One Academic. (2029263358). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/cultural-imprint-history-northwest-coast-native/docview/2029263358/se-2