A true artistic polymath, William Kentridge has spent the past four decades developing a body of work that incorporates conceptual and collaborative practices, produced and exhibited in his home country of South Africa and around the world.

Kentridge is best known for his prints, drawings, and films that engage with complicated historical legacies of violence and oppression. In particular, his work is strongly informed by growing up under the apartheid regime in Johannesburg, South Africa. His work serves as allegories of the human condition and our relationship to the world at large.

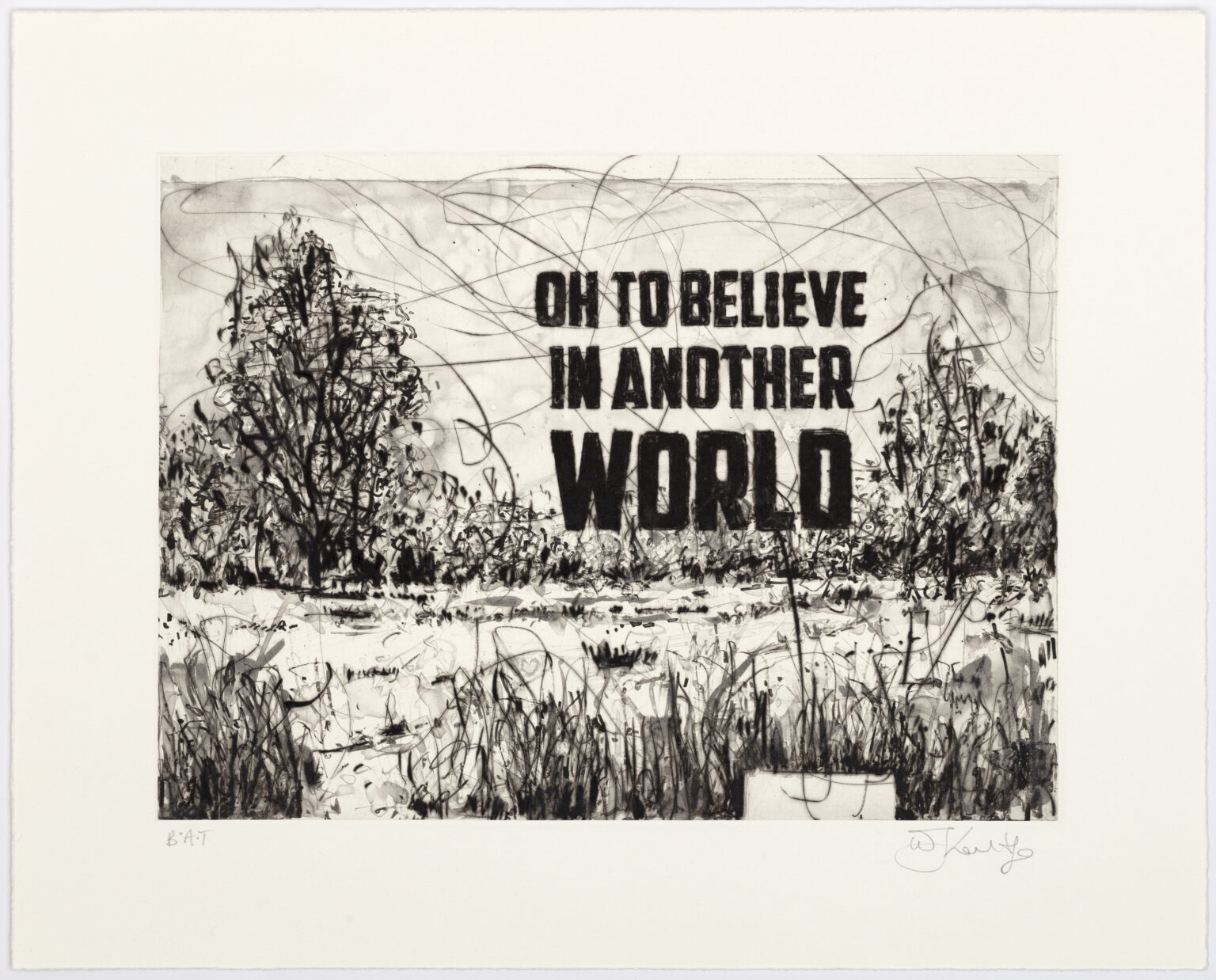

Active since the 1970s, Kentridge’s practice is rooted in avant-garde theatre and politically-engaged modernist art from the early twentieth century. He became known for a sequence of hand-drawn animated films during the 1990s which were constructed by filming a drawing in process, making erasures and changes, and then re-filming it. Through this meticulous process, drawing becomes a field for transformation.

Key to Kentridge’s practice is his collaboration with his printmakers, one of which is featured on ArtRow: Master Printer Jillian Ross. Currently on display at the Remai Modern in Saskatoon is the exhibition Live Editions that showcases Jillian Ross Print and re-creates the space of Ross’s studio to demonstrate the deeply collaborative nature of Kentridge’s printmaking practice. The exhibition offers a glimpse into the complex and nuanced relationship between the artist and the master printer – a collaboration that not only makes these works possible, but also successful. Kentridge refers to his prints (and other mediums) as “translations.” Like a language translated, each new piece takes on fresh meaning.

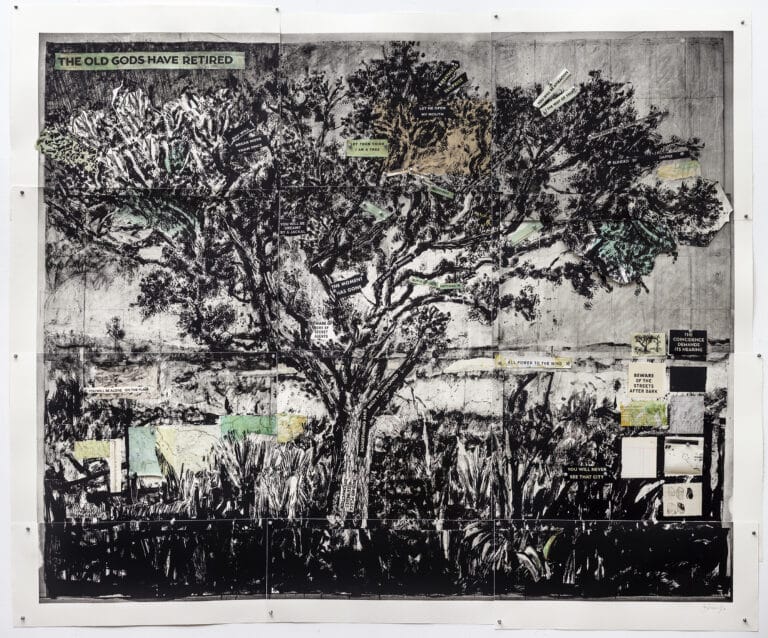

Old Gods Have Retired

ArtRow is thrilled to present one of Kentridge’s recent print editions, Old Gods Have Retired, a large-scale print “translation” of an original mixed media piece that covered an entire wall in Kentridge’s Johannesburg studio. True to form, Kentridge and his team used multiple mediums and processes to create the monumental work consisting of 12 sheets, including photogravure, sugarlift aquatint, direct gravure, drypoint, handpainting, and collage.

In Old Gods, a tree juts against an expanse of grey sky as its branches extend upwards and outwards, filling the composition of this monumental limited edition print. Layered over the image are fragments of found ledgers from an early twentieth century encyclopaedia, fragments of maps, hand-painted figures, and dislocated texts that interrupt the continuity of the image. Phrases such as “let them think I am a tree” and “reminds me of something I can’t remember” mingle in-between the branches, creating a visual play that evokes the tree as a metaphor for how we experience the world: we piece together fragments of objects, memories, and experience to form a complex, if incomplete, whole.

Collaboration and Artistic Versatility

Old Gods Have Retired was imagined, worked and reworked, and ultimately realized by five studios in collaboration: a photogravure studio in Cape Town; Kentridge’s studio; the David Krut printmaking studio in Johannesburg; Ross’s studio in Saskatchewan; and, the printmaking department at the University of Alberta. This collaborative approach is a staple of Kentridge’s work and cannot be distilled from the results of his artistic projects.

In many working relationships, the distinction is clear: a printmaker is an artist who carries out all the steps solo, from designing to carving the woodblock, lino, or copper plates, to mixing the inks and pressing the paper. Each step requires technical expertise as well as artistic vision.

The artistic relationship between Kentridge and Ross is more nuanced than artist and printer. Both recognize that their collaboration is an inextricable layer that cannot but deeply impact the outcomes of an artistic project – rather than a necessary byproduct of large-scale print production. Ross has worked with Kentridge for decades, and her expertise and willingness to experiment with the process leads to trajectories that would never have come to light if either creator was working independently.

That Ross is not Kentridge’s only collaborator serves to further intensify the conceptual role that the process plays in all of the artist’s works. The realization of Kentridge’s ideations—carving unique linocuts to be printed onto more than 100 sheets of dictionary paper or 27 intricate copper plates—often calls for a dozen or more printers and technicians and, still, even one takes around four years to complete. Every individual who prepares a sheet of paper for the press, who proposes a different colour, or wood, or depth of an etched mark, impacts the outcome of the project. Even the press itself has a role to play, producing a mirrored version that never fails to surprise or delight printers and artist alike.

It quickly becomes clear that it is impossible to call Kentridge’s work “just” print editions. The process is inextricably linked to the finished works as each hand and mind involved in the collaboration is embedded in the work. As Ross explains, each piece is “a part of the conversation of how art gets made.”