Pop Art, the broadly recognized art movement that began in the 1950s and is synonymous with Warhol’s Brillo boxes and Campbell’s soup cans, drew inspiration from popular and commercial culture to reach mass audiences—a notable departure from more esoteric and lofty art movements such as abstract expressionism. Indeed, many modernist art critics were appalled by the use of such “low” subject matter as canned goods and comic books.

Pop artists used the reproduction of identifiable subjects for which the movement is known to make powerful statements about the state of the world and the growing power of consumerism. Many images playfully or irreverently exploited the ever-increasing ease of mass production that the US, in particular, experienced following the war.

Many American artists are celebrated today for their lasting impact on the art world in a new and accessible way. The printmaking of artists like Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann, Keith Haring, and others continues to be highly sought after by collectors around the world.

ArtRow is delighted to feature some of these iconic artworks. It doesn’t feel like a stretch to assume that these groundbreaking creators would wholly appreciate the dissemination of their art moving into the digital sphere.

The Emergence of Pop Art in North America

Pop Art originated in Britain in the 1950s, rooted in Neo-Dadaism and other movements that questioned what makes something “art.” It was quickly adopted and adapted by American artists, who found huge potential in the prospect of elevating the commonplace.

After WWII, the United States was immersed in an unprecedented economic boom. People moved out of the cities into suburbs populated with mass-produced, cookie-cutter homes—just one example of the conformity Americans eagerly adopted. Artists began pursuing new ways of fighting what they considered a stifling social order made ubiquitous by the cheap production of goods—everything from canned foods to houses and cars.

Many of these artists were also acting in opposition to previously lauded art styles, namely Abstract Expressionism. Realistic portrayals of the mundane were the new choice models, and these were often laced with irony and societal critique.

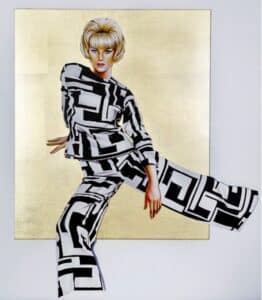

While Pop Art may have appeared to wholeheartedly throw out the old to usher in the new, artists like Warhol and Lichtenstein maintained a link to art styles of the past, upholding fine art traditions as they turned out representations of mass media. They merged traditional mediums like painting and handmade goods with printmaking and mass-produced products. They drew from objects and imagery as well as text to bestow new meaning on the products and visuals with which society was already steeped. While each artist put their own unique spin on Pop Art, a number of coherent themes and practices emerge when we step back and view the movement as a whole.

Mass Media and Consumer Culture

Consumer goods reached new heights of ubiquity after the economy exploded in the 1950s and 60s. Pop artists saw in the rising saturation of advertising imagery and mass consumption an opportunity to challenge—or at least reflect—these new consumer-driven values.

Artists like Warhol adopted commercial art techniques, such as screen printing, along with their images. The result was pieces like his instantly recognizable Campbell’s Soup cans, the perfect example of the commonplace being raised to the echelons of high art. Warhol is also known for his portraits of cult celebrity figures like Marilyn Monroe, Jackie Kennedy Onassis, and Blondie, which echoed the surging accessibility of celebrity photographs in every drugstore magazine.

Andy Warhol, Geronimo, From Cowboys and Indians, 1986

Bold, Graphic Aesthetics

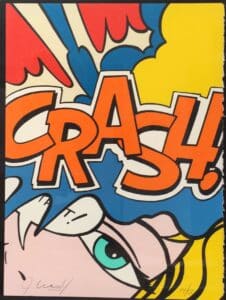

Pop Art motifs could also stretch beyond advertising and celebrity culture. Artists like Roy Lichtenstein and John Matos turned to the comic book, which was already at peak popularity and had faced its own battles with censorship in the past decade. Using commercial illustration techniques like Ben-Day dots and bold flat colour and incorporating text, they mimicked the skillful aesthetic and highlighted the arbitrary division between “fine art” and everyday imagery.

Works like those of Lichtenstein and more recently John Matos, critique mass consumerism while also seeming to challenge the traditional art values that held that anything widely distributed could not be art.

In later years, artists continued to adopt these bold colour palettes and reductive lines into art making. In the 1980s, Keith Haring upheld the accessibility and commercialism of the movement when he opened the Pop Shop to sell reproductions of his bright, faceless but highly animated characters, which were printed onto shirts and pins. Today, his barking dog and “wiggling” human forms remain highly recognized. Tom Wesselmann exhibited strong outlines in an homage to classical reclining nudes, such as Rosemary Lying on One Elbow, which transforms industrial steel welding into art.

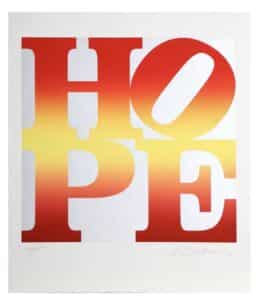

Social Commentary & Political Messages

Pop artists approached social commentary in their work in different ways. From artists like Jeff Koons, who asserts that his sculptures and images of nostalgic items have no ulterior motive, to clear commentaries in the works of Robert Indiana and Keith Haring’s Free South Africa, artists took to the picture plane to address systemic issues in the realms of race, sexuality, and hope for the future.

Repetition and Reproduction

If a product isn’t easily reproducible or plentiful, it fails as a commodity. Pop artists embraced this requirement, which fit neatly into the printmaking processes many of them were exploring. Using repeatable materials like silkscreens and carved or etched surfaces, they could create hundreds of the same design, yet still impart each print with some degree of uniqueness.

Warhol’s Dollar Sign exemplifies both this repetition and reproduction. He repeated the visual in multiple ways, and many of the images were reproduced using different colours and patterns. It’s a not-so-subtle statement about the intertwining of art and commerce.

The Lasting Influence of Pop

Collectors continue to covet Pop and we are honoured to feature works by some of the foremost artists of the movement, including Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, and Mel Ramos. Not only do the creations of Pop artists from the 60s, 70s, and 80s still evoke great interest from art lovers and collectors today, but the practice itself has also continued. This is, perhaps, understandable, considering the widespread worship of consumerism and mass production that still permeates our modern era.

The ongoing resonance of Pop Art catalyzed movements to come later. Street Art evolved out of urban graffiti, which has long insisted that art should exist outside of laws, property, and ownership—that it should be democratic and empowering. It’s not hard to draw a link between these tenets and Pop Art’s elevation of everyday subject matter to the level of high art.

Postmodernism, and the associated Neo Pop style, also follow in the footsteps of this groundbreaking movement. Gaining popularity in the 1980s and 90s, Neo Pop embraced the commercial and kitsch aspects of Pop Art while expanding its selection of subjects and techniques. Ongoing links between Pop Art and fashion, comic books, graffiti, and other art forms that eschew the traditional art gallery for ordinary communal spaces continue to remind the world that art isn’t just for the affluent and their hallowed halls. It’s for everyone.