As a self-proclaimed fashion enthusiast, an interest that feels very much aligned with my similar attentiveness for all news art-related, I was just as excited for the opening of ‘Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion’ as I was for the livestream of this year’s Met Gala. I remember reading about the theme a few months ago and wondering how such a delicate, yet organic theme would be interpreted by designers and curators alike.

The Costume Institute’s spring show draws inspiration from the classic fairytale Sleeping Beauty, a story of a princess who enters eternal slumber, a curse only able to be broken by a true love’s kiss, before waking up a century later after a fateful encounter with a Prince. Upon doing some research, I learned that this exhibition also, in some ways, pays homage to motifs found in 17th-century English poetry and intertwined metaphors of nature, life, and beauty. While the title of the exhibit could connote a degree of passivity as opposed to exhilaration, it is this connection to the natural world that animates the circularity of fashion, as an agent bound to seasonal changes, elemental ornaments, and earthly ephemera.

Perhaps, with hopes this high, I was bound to be at least slightly disappointed.

A Long Wait and a Long Walk

To preface, I want to give a brief walkthrough of the show itself. When I first entered the Met, I naively ignored the posters and banners advertising the exhibit and made a direct beeline for the Costume Institute, where I assumed the show would be. After some confusion and redirection, I found myself in the second floor of the museum, faced with a QR code I had to scan to enter a waiting list to see the show. This ended up taking an hour and a half, which is actually on the shorter end of the timeframe (on busier days, you might have to wait all day). Yet, by this point, I felt like I was some knock-off version of Sleeping Beauty herself, fighting off eternal slumber through muffled yawns and desperate sips of an iced coffee long emptied.

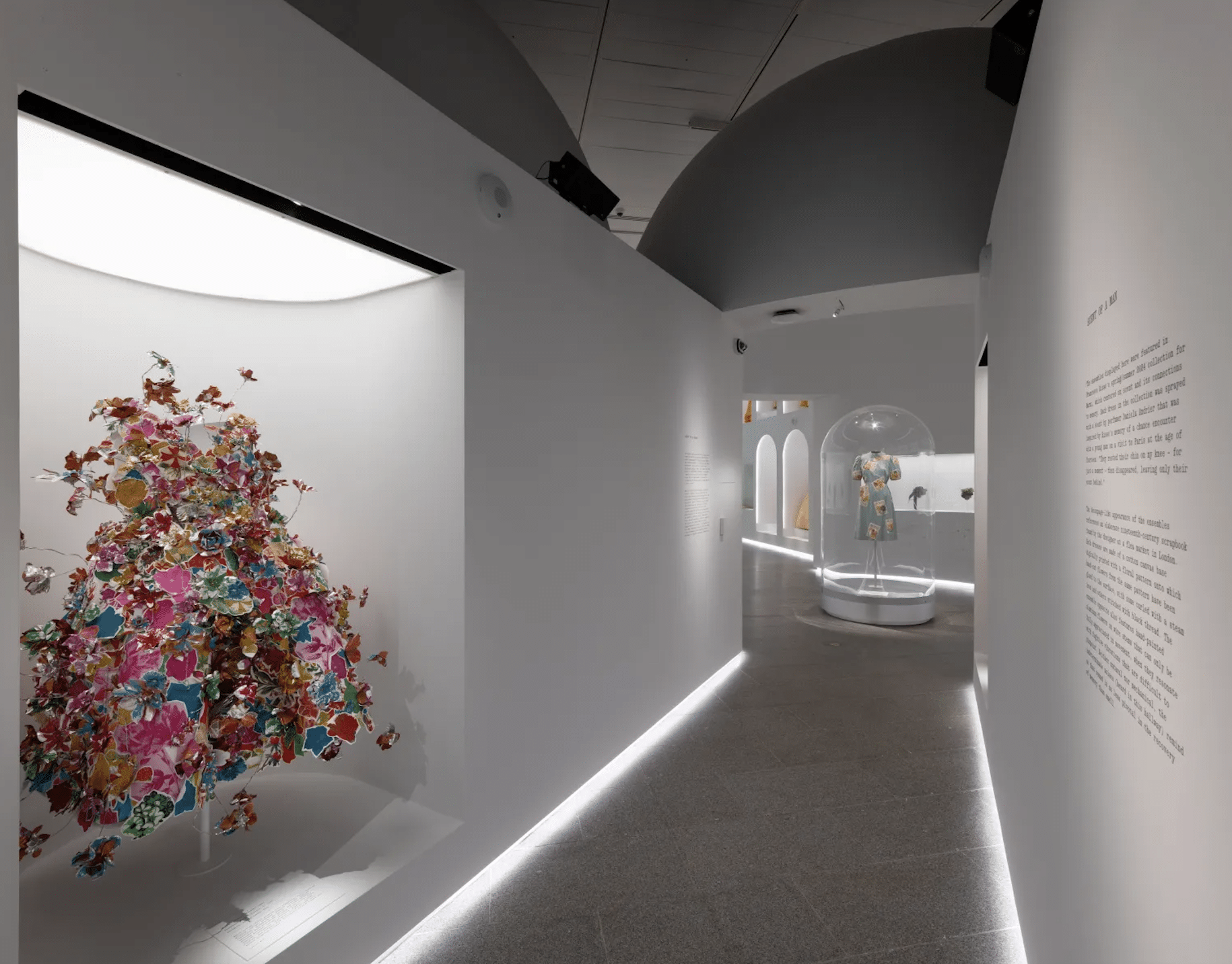

As I entered the exhibit, I quickly understood why it had to be relocated from the original Costume Institute location. With over 200 pieces dispersed across over 20 rooms, there was an endless selection of works to peruse. To a certain extent, it felt almost too congested, especially given the influx of passersby browsing the rooms. While moments of pause are generally appreciated when attending a museum or gallery show, as these periods are crucial to truly taking in the material and thematic impact of a work, the “pause” perpetuated by ‘Sleeping Beauties’ felt imposed against my will. In my flustered and half-awake state, I could never find a right moment to take out my phone and document the show, as I already felt enough pressure to keep the (slow) flow of the show going as is.

Heavy on the Historic Exposition

This brings me to my first critique of the show. While in many ways the executed scope and range of ‘Sleeping Beauties’ is exactly its ethos, and should thereby be applauded, I felt that this over-saturation of space diluted the impact of the historicity being presented. There is a special kind of power to things left unsaid that this show could have potentially benefited from, one that mediates, as opposed to instructs, learning on the viewer’s own terms through a curatorial narrative that gives room for breath.

I also have mixed feelings about the ‘The Scent of a Woman’ section, which revives the scent of Millicent Rogers by extracting and replicating molecules of her body, environment, and perfume. This process was conducted by smell artist Sissel Tolaas in collaboration with architect Dominic Leong. In spite of its cutting edge technology, this portion of the exhibit read as more clinical than transformative. There was an uncomfortable, fetishistic quality to smelling aromas that should have been long made unavailable, a salient sentiment that lingered long after the curated scents had faded.

However, there were some truly amazing features in this show amidst the floral fabrics and Bridgerton-esque ballgowns. My personal favorites include unearthed gems from the archives of Alexander McQueen and Iris Van Herpen, two of my most beloved designers, as well as various robes à la franchise, offering a glimpse into historical galas dating back to the mid-1700s. The similar finesse of craftsmanship traced between each costume despite their chronological and geographical stratification was truly mesmerizing. It highlights how the role of fashion has not only progressed throughout the ages but also remained the same in many ways (for better and for worse): as a mode of self-expression, a claim to status mobility or lack thereof, and an epitomization of the intersection of art and life.

Namesakes in Reclined Composure

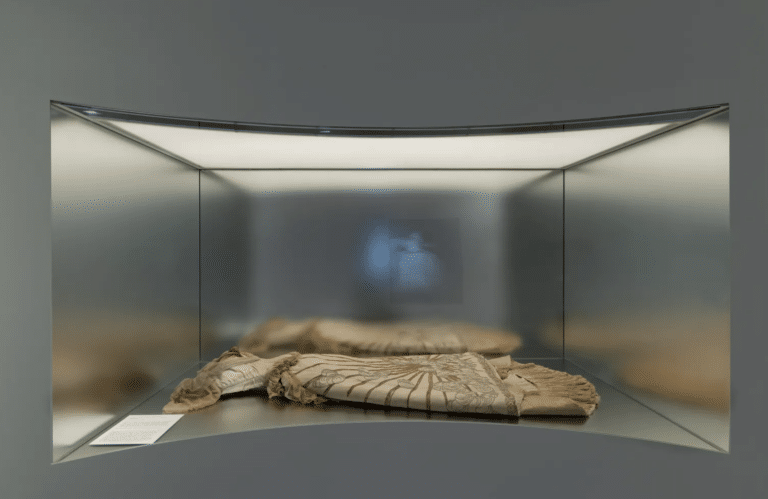

There’s been a lot of debate over the efficacy of the ‘sleeping beauties’ themselves, which consist of sixteen special, highly delicate garments that are on the brink of disintegration due to their age. Due to such conditions, these pieces cannot be displayed on mannequins and are instead presented in glass coffins, where they lay horizontally. There are some who express disappointment over this installation method, stating that they resemble corpses in their flat, one-dimensional state, unable to be imagined as brought to life and worn on the body.

Personally, however, I was drawn to these works due to their embodiment of a certain kind of memento mori, a reminder that nothing lasts forever, that even the most beautiful vessels can shatter when pushed off the pedestal of their designated epoch, that while there might be a rainbow after the rain, there will also be unavoidable weathered decay after said storm.

At its best, ‘Sleeping Beauties’ treads a whimsical line between historical folklore and modern extravagance, between otherworldly Shakespearean hallucinations in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and trailblazing designs that could very well be imagined in an alternate Met Gala. Perhaps one takeaway from this exhibit is that florals will never truly exit the trend cycle. Perhaps another is that fashion will always have a place in history, just as it acts as a reminder of history itself, both in the museum and in the habitual enclaves of our everyday ecosystems.

Linda Dai

Linda is a contemporary art aficionado based in New York. She earned her BA in Media Studies and Politics from Pomona College and is currently pursuing an MA in Modern and Contemporary Art: Critical and Curatorial Studies (MODA) at Columbia University. She is interested in critical and curatorial themes of space, time, and memory, especially surrounding works that infuse a plethora of old/new media. Linda has worked with various galleries and media groups in New York and Los Angeles. In addition to her contributions to ArtRow, she serves as a Head Editor for the MODA Critical Review and is an affiliated representative for the Crossing Art Collective.