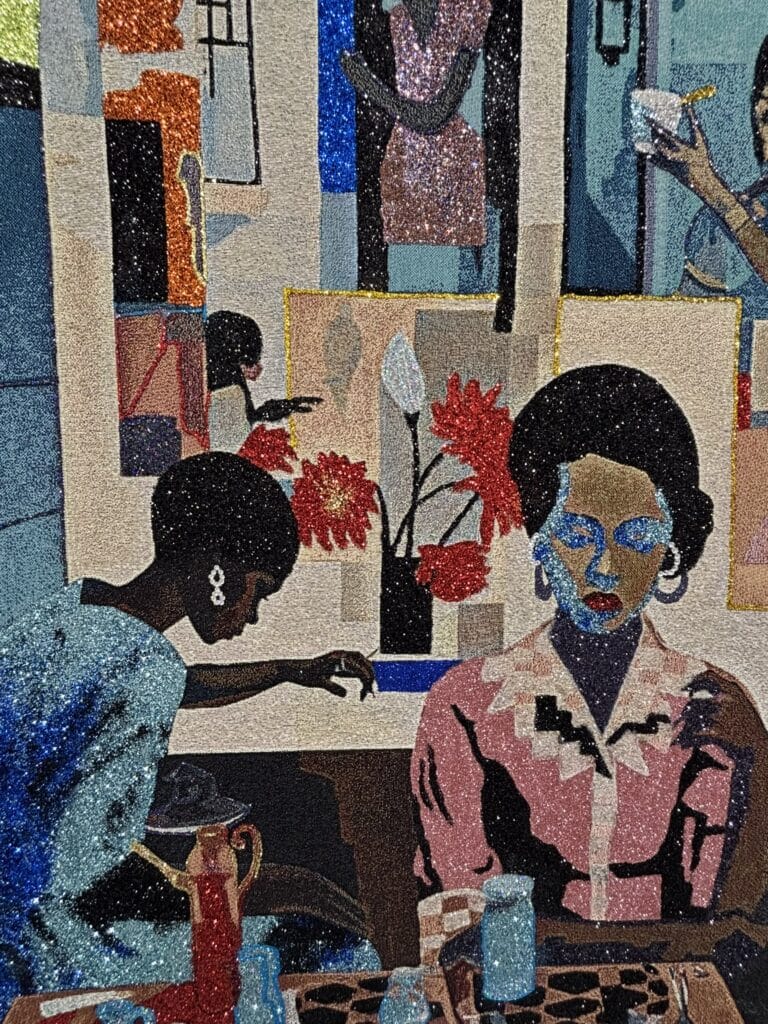

Marika St. Rose Yeo’s Shifting Conversations sculpture series explores “the premise of search, the act of seeking out traces of things left behind, and information and memory transmitted through the materiality of earth.” The artist draws from her diverse cultural background as a Caribbean Canadian and her PhD in Critical and Creative Social Justice Studies to create ceramic vessels that “emphasize vulnerability and fragility.”

Yeo’s work is also inspired by the words of Derek Walcott, a poet, playwright, and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Speaking of gathering and assembling pieces of our fractured ancestry in a Nobel lecture, Walcott said “break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole.”

The act of examining and piecing together histories to assemble stronger, more meaningful reconstructions is a salient concept beyond Yeo’s captivating sculptures, one that informs how we consider identity and the associated themes of healing, immigration, and the diaspora.

An Analogy of Fragility and Healing

It is not only the once-shattered nature of Yeo’s Shifting Conversations sculptures that speaks to fragility and healing—it is also her choice of medium. Ceramics have an inherent fragility about them, born of their delicacy and the importance often placed on such heirlooms by our forebearers.

As Walcott’s quote suggests, reassembling pieces of our pasts or the pasts of our adopted and native homes sheds light on both the fragility of our histories and the resilience that makes those pieces capable of being put back together. Likewise, that resilience applies both to the history itself and to the contemporary person who is seeking and facilitating this reconstruction, all the while discovering (or re-discovering) the trauma and the healing inherent in uncovering stories and putting oneself and one’s history together again.

The Immigrant’s Conflicted Reconstruction

The link between broken pieces and immigration is also a compelling one. Whether an individual represents the first or fifth generation of their family in a country other than their ancestral home, the pieces left behind—not only in their home country but also at every point along the journey to the current place—compose a fractured history that reveals a full picture only when reassembled, through research, family interviews, visits to the ancestral home, and interactions with those of the same cultural background.

To an outsider, the work people do to achieve this rebuilding is presumed to be validating, invigorating, and affirming. Often, though, it also carries with it the traumas of the circumstances that necessitated the exodus in the first place, as well as the trials encountered along the way.

The resulting construction of these fragments—for those who can endure the exploration and are able to access the necessary resources to compile a cohesive narrative—is a juxtaposition of joy and grief, tragedy and achievement, that might very well feel like an overlapping and slightly mismatched sculpture, even as it succeeds in creating something whole and revealing. That plurality, felt by so many immigrant people, is made manifest in Yeo’s impactful visuals.

Fitting In As Diaspora

However whole and revealing the final construction might be, there will always be layers and cracks, patterns that don’t quite fit—perhaps even leaks that make these deeply earnest vessels incapable of holding water. This is the almost inescapable result of trying to make a life fit where it cannot, by its very nature, be puzzle-piece-perfect. As many individuals in diasporic communities chronicle, it takes a great deal of effort to identify where they fit within the existing mold of a new culture, even one as multicultural as North America.

The balance of “fitting in” and maintaining a certain cultural identity—regardless of which culture the individual was raised within— results in folds, overlaps, and gaps where identity and expectation may never quite fit together. Often, diasporic communities are expected to reflect the culture of their heritage and simultaneously embrace the culture of their current home. As time goes on, these layers remain in flux, shifting to open new gaps and cracking to adjust to new expectations—both their own and those of their community. Yeo’s sculptures remind us of the difficulty and the beauty of the constructions immigrants and refugees build as they seek a place in a society often unwilling to shift for them.

Upholding Identity in Art

Yeo’s sculptures embrace gathering and re-making as acts of navigating and refining identity through art. The creative process itself is often cited as a therapeutic and affirming approach to understanding and expressing these concepts, both for the person undertaking it and the viewers, readers, or listeners who will experience the results of that process.

Artwork that speaks to identity comes in as many forms as the people who create it. The final product of some of these forms is more accessible than others. The visual impact of broken and reconstructed vases welcomes myriad ideas around original objects, shattered fragments, the act of rebuilding, and how the meaning of the rebuilt object differs from the original. All of these feel tangible and open the discussion to questions: who or what was broken, who or what broke it or them, the intention behind the reconstruction, and so much more.

Marika St. Rose Yeo’s Shifting Conversations series is an impactful, beautiful, and probing representation of the act of searching for what has been lost or left behind, gathering these disparate parts, and piecing them back together. Her work incorporates the strength and fragility of immigration, diaspora, plurality, and identity politics, and the people these themes affect, with an astute and skillful hand.

ArtRow is honoured to feature Shifting Conversations 1 and, in promoting it, we seek to facilitate discussions around these topics and to recognise Yeo as an emerging artist of great talent.

Marika St. Rose Yeo