Though she painted and wrote more than 80 years ago, Emily Carr remains a pillar of Canadian art and a much-discussed figure in the discourse on modernism, male dominance in art, and Indigenous appropriation.

The visual impact of Carr’s art endures and contemporary conversations about the (colonial) portrayal of Indigenous cultures maintain the relevance of her work. Art and literature lovers alike devour her journals, and galleries continue to showcase her paintings and sketches. The Vancouver Art Gallery recently refreshed its Carr collection through a new installation entitled “A Room of Her Own,” a concise and pointed illumination of her work on paper and on canvas and the iconic tropes that are repeated in her visual representations.

Born in 1871 in Victoria, British Columbia, Carr fostered a deep connection to the landscape and Pacific Northwest Indigenous cultures throughout her life, as evidenced in her most famous paintings and her journals. Carr’s artistic training combined her European heritage and a deep love for her West Coast homeland. She studied in San Francisco, England, and France, and it was modernist painters like Harry Phelan Gibb and the Group of Seven that ultimately caught her eye and inspired her hand.

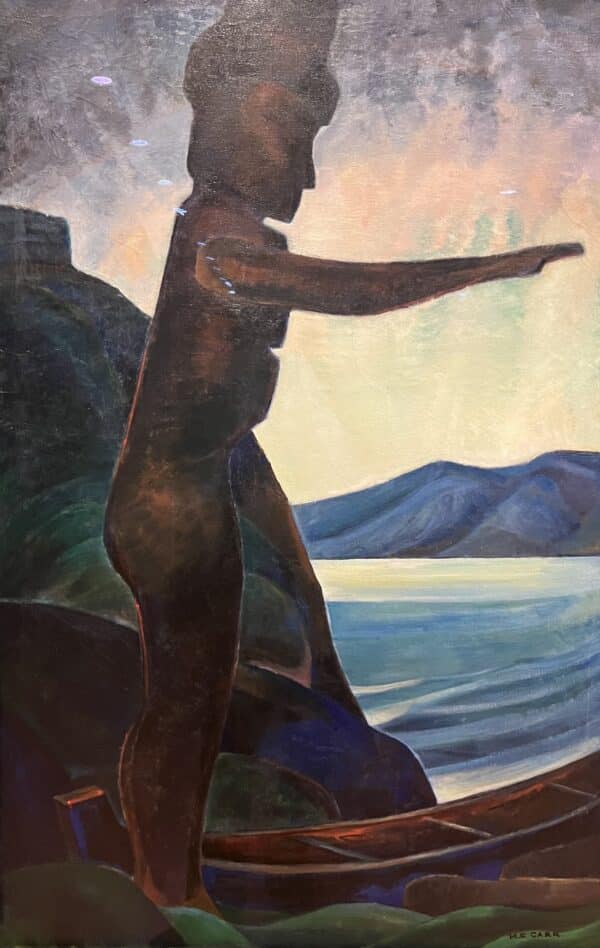

When she returned home, Carr imbued her passion for the Canadian landscape and the Indigenous communities she often visited with this style, employing vibrant colors and dynamic compositions in her depictions of the forests and Indigenous communities of Western Canada.

A Modernist Pioneer in a Male-Dominated Era

Carr’s use of the modernist artistic voice is one reason she remains such a prolific figure today. The modernist movement was heavily dominated by men, with only a few female artists—such as Frances Hodgkins and Georgia O’Keefe—breaking into this early-20th-century artistic brotherhood.

Ascending to acclaim as a female artist at this time was, in itself, no small feat. Rather than the motherly portraits of Mary Cassatt or the luscious abstract florals of O’Keefe, Carr threw herself into landscapes—in the style of some of the male modern masters of the time. She made the bold verticals, swirling skies, and rich motion of the Group of Seven her own, to such success that she was invited to exhibit alongside them in the early 1930s.

Controversy and Conversation: Cultural Representation and Appropriation

The question of whether Emily Carr expanded the appreciation of or appropriated Indigenous cultures with her paintings of Pacific West Coast villages and totem poles is not a new one. The cover story of a 1993 issue of Canadian Art magazine featured the debate, stating Carr was “the first to do for [the totem poles of coastal BC] what Picasso did for the African sculpture he encountered around the same time, and what Gauguin earlier did for Tahitian art: she could take them imaginatively out of their own milieu and exhibit their virtues within another culture.”

Carr and her contemporary fellow artists and supporters would never have considered those paintings appropriation, but today many critics ask whether ignorance absolves them. The article notes that Carr’s European/Canadian upbringing and lived experience made it impossible for her to consider the Indigenous populations she met from anything but a European perspective. In these discussions, some Indigenous scholars today use Carr as an example of white imperialism, then and now.

Paintings like “The Big Raven,” which is included in VAG’s extensive collection, epitomize both Carr’s undeniable skill and her amalgamation of Group of Seven-esque style and Indigenous portrayal. That the Group of Seven has also been criticized—for depicting a pristine Canadian landscape untouched by even the humans who have resided on this land for millennia—does not go unremarked by critics of Carr and other artists. Carr’s pieces recognize this inherent Indigenous proprietorship while the Group of Seven did not—but does this make them less eligible for accusations of appropriation?

Proponents of Carr’s pioneering work and her intentions cite the genuine respect for the Indigenous communities with which she interacted and her great effort to understand and preserve their stories and traditions in her writing. The question, then, becomes whether a child of European immigrants has the right to be that voice for another culture.

Whatever one’s perspective, there is no question that the continued relevance of Emily Carr’s work contributes to the necessarily ongoing discussion of Indigenous identities, appropriation, and reparations.

Emily Carr in the 21st century

Carr’s influence extends beyond her contributions to modernist painting. As a writer, her autobiographical works provide insightful reflections on her life, art, and the landscapes that inspired her. She put forth an environmental perspective that is important in a time so heavily influenced by urgent discussions around climate change.

Carr’s enduring popularity in Canada, and beyond, is a testament to her role as a female pioneer of modernist art and an important figure in the narrative of Canadian identity. Her work and life story continue to inspire artists, writers, and thinkers to explore the rich tapestry of Canada’s cultural heritage and the dynamic interplay between land, gender, identity, and art.